|

|

Conference Location

History

|

The earliest origins of Lincoln can be traced to the remains of an Iron Age settlement of round wooden dwellings (which were discovered by archaeologists in 1972) that have been dated to the 1st century BC. This settlement was built by a deep pool (the modern Brayford Pool) in the River Witham at the foot of a large hill (on which the Normans later built Lincoln Cathedral and Lincoln Castle). The origins of the name Lincoln may come from this period, when the settlement is thought to have been named in the Brythonic language of Iron Age Britain's Celtic inhabitants as Lindon "The Pool", presumably referring to the Brayford Pool (compare the etymology of the name Dublin, from the Gaelic dubh linn "black pool"). It is not possible to know how big this original settlement was as its remains are now buried deep beneath the later Roman and medieval ruins, as well as the modern Lincoln. |

|

| Roman history: Lindum Colonia

The Romans conquered this part of Britain in AD 48 and shortly afterwards built a legionary fortress high on a hill overlooking the natural lake formed by the widening of the River Witham (the modern day Brayford Pool) and at the northern end of the Fosse Way Roman road (A46). The Celtic name Lindon was subsequently Latinized to Lindum and given the title Colonia when it was converted into a settlement for army veterans. |

||

AD 410–1066

|

During this period the Latin name Lindum Colonia was shortened in Old English to become 'Lincylene'. After the first destructive Viking raids, the city once again rose to some importance, with oversea trading connections. In Viking times Lincoln was a trading centre that issued coins from its own mint, by far the most important in Lincolnshire and by the end of the 10th century, comparable in output to the mint at York. After the establishment of Dane Law in 886, Lincoln became one of The Five Boroughs in the East Midlands. Excavations at Flaxengate reveal that this area, deserted since Roman times, received new timber-framed buildings fronting a new street system, ca 900. Lincoln experienced an unprecedented explosion in its economy with the settlement of the Danes. Like York, the Upper City seems to have been given over to purely administrative functions up to 850 or so, while the Lower City, running down the hill towards the River Witham, may have been largely deserted. By 950, however, the banks of the Witham were newly developed with the Lower City being resettled and the suburb of Wigford quickly emerging as a major trading centre. In 1068, two years after the Norman conquest, William I ordered Lincoln Castle to be built on the site of the former Roman settlement, for the same strategic reasons and controlling the same road |

|

|

Medieval town

During the Anarchy, in 1141 Lincoln was the site of a battle between King Stephen and the forces of Empress Matilda, led by her illegitimate halfbrother Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester. After fierce fighting in the city's streets, Stephen's forces were defeated. Stephen himself was captured and taken to Bristol. By 1150, Lincoln was among the wealthiest towns in England. The basis of the economy was cloth and wool, exported to Flanders; Lincoln weavers had set up a guild in 1130 to produce Lincoln Cloth, especially the fine dyed 'scarlet' and 'green', the reputation of which was later enhanced by Robin Hood wearing woolens of Lincoln green. In the Guildhall that surmounts the city gate called the Stonebow, the ancient Council Chamber contains Lincoln's civic insignia, probably the finest collection of civic regalia. Outside the precincts of cathedral and castle, the old quarter clustered around the Bailgate, and down Steep Hill to the High Bridge, which bears half-timbered housing, with the upper storeys jutting out over the river. There are three ancient churches: St Mary le Wigford and St Peter at Gowts are both 11th century in origin and St Mary Magdalene, built in the late 13th century, is an unusual English dedication to the saint whose cult was coming greatly into vogue on the European continent at that time. Lincoln was home to one of the five most important Jewish communities in England, well established before it was officially noted in 1154. In 1190, anti-semitic riots that started in King's Lynn, Norfolk, spread to Lincoln; the Jewish community took refuge with royal officials, but their habitations were plundered. The so-called 'House of Aaron' has a two-storey street frontage that is essentially 12th century and a nearby Jew's House likewise bears witness to the Jewish population. In 1255, the affair called 'The Libel of Lincoln' in which prominent Jews of Lincoln, accused of the ritual murder of a Christian boy ('Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln' in medieval folklore) were sent to the Tower of London and 18 were executed. The Jews were expelled en masse in 1290. During the 13th century, Lincoln was the third largest city in England and was a favourite of more than one king. During the First Barons' War, it became caught up in the strife between the king and the rebel barons, who had allied with the French. It was here and at Dover that the French and Rebel army was defeated. In the aftermath of the battle, the town was pillaged for having sided with Prince Louis. During the 14th century, however, the city's fortunes began to decline. The lower city was prone to flooding, becoming increasingly isolated, and plagues were common. In 1409, the city was made a county corporate. |

|

|

16th century

|

The Dissolution of the Monasteries exacerbated Lincoln's problems, cutting off its main source of diocesan income and drying up the network of patronage controlled by the bishop, with no fewer than seven monasteries closed down within the city alone. A number of nearby abbeys were also closed, which led to a further diminution of the region's political power. When the cathedral's great spire rotted and collapsed in 1549 and was not replaced, it was a significant symbol of Lincoln's economic and political decline. However, the comparative poverty of post-medieval Lincoln preserved pre-medieval structures that would probably have been lost in a more prosperous scenario. |

|

|

Civil War

Between 1642 and 1651, during the English Civil War, Lincoln was on the frontier between the Royalist and Parliamentary forces and changed hands several times. Many buildings were badly damaged. Lincoln now had no major industry and no easy access to the sea and was poorly situated. Thus while the rest of the country was beginning to prosper at the beginning of the 18th century, Lincoln suffered immensely, travellers often commenting on the state of what had essentially become a 'one street' town. |

|

|

Georgian Age and Industrial Revolution

|

By the Georgian era, Lincoln's fortunes began to pick up, thanks in part to the Agricultural Revolution. The re-opening of the Foss Dyke canal allowed coal and other raw materials vital to industry to be more easily brought into the city. Coupled with the arrival of the railway links, Lincoln boomed again during the Industrial Revolution, and several world-famous companies arose, such as Ruston's, Clayton's, Proctor's and William Foster's. Lincoln began to excel in heavy engineering, building diesel engine locomotives, steam shovels and all manner of heavy machinery. |

|

|

20th century

In the world wars, Lincoln switched to war production. The first ever tanks were invented, designed and built in Lincoln by William Foster & Co. during the First World War and population growth provided more workers for even greater expansion. The tanks were tested on land now covered by Tritton Road (in the south-west suburbs of the city). During the Second World War, Lincoln produced a vast array of war goods, from tanks, aircraft, munitions and military vehicles. This heavy industry became a mainstay of Lincoln's economy and even despite the decline of heavy industry towards the end of the 20th century, mimicking the wider economic profile of the United Kingdom, more people are now still employed today in Lincoln building gas turbines than ever before. |

|

Parts of this text were copied from

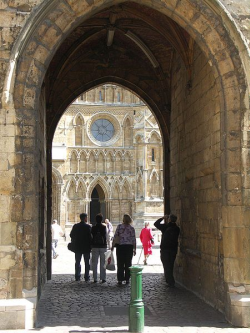

Conference Venue

|

University of Lincoln |

How to reach Lincoln and the conference venue

By Plane |

When arriving by plane in the UK you are mostly destined to arrive in London either at Heathrow, Stansted, Gatwick or Luton Airport. From these airports you need to make your way by train or tube to Kings Cross Station from where you can take a direct train to Lincoln. (journey time 2 hours) |

By Train |

When taking the train to the United Kingdom, you will be using the EUROSTAR service arriving at St.Pancras station. After clearing customs and passport control you leave the station and enter Kings Cross Station from where you can take a direct train to Lincoln. (journey time 2 hours) |

By Bus |

A number of coach companies travel to and from Lincoln from most major cities, such as National Express. |

By Taxi |

Several taxi companies are in operation in the Lincoln area. Follow this link for their contact information. |

By Car |

Lincoln is a little over 150 miles from London. The journey by car takes just over three hours. Road access is via the A1 with intersections at Newark (A46) from the South and near Retford (A57) from the North. The city is 40 miles east of Nottingham on the A46 and 40 miles south of the Humber Bridge on the A15. |

BEWARE

When you bring your PC or other equipment to the UK be aware that different plugs are needed. (see an overview of world plugs here)

- That your VISA requirements are OK. See the Fees Page for more information.

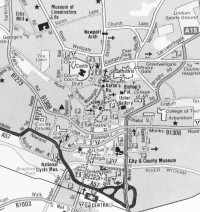

Location Maps

|

|

|

Click on the above maps for a more detailed view

This is a detailed link and map of the Brayford Pool campus, which can also be downloaded in pdf format. (800Kb)

Useful links

Check back for further updates here:

Tel: +44 (0)1522 882 000

Tel: +44 (0)1522 882 000