|

Valencia, is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third largest city in Spain after Madrid and Barcelona, with around 800,000 inhabitants in the administrative centre. Its urban area extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of around 1.5 million people. Valencia is Spain's third largest metropolitan area, with a population ranging from 1.7 to 2.5 million. The city has global city status. The Port of Valencia is the 5th busiest container port in Europe and busiest container port on the Mediterranean Sea. Valencia, is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third largest city in Spain after Madrid and Barcelona, with around 800,000 inhabitants in the administrative centre. Its urban area extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of around 1.5 million people. Valencia is Spain's third largest metropolitan area, with a population ranging from 1.7 to 2.5 million. The city has global city status. The Port of Valencia is the 5th busiest container port in Europe and busiest container port on the Mediterranean Sea.

|

|

|

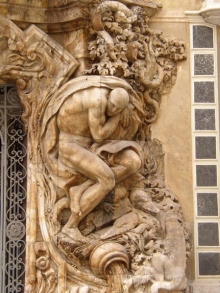

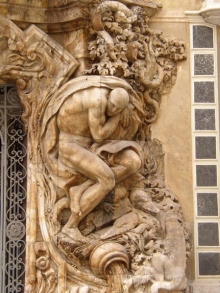

Its historic centre is one of the largest in Spain, with approximately 169 hectares; this heritage of ancient monuments, views and cultural attractions makes Valencia one of the country's most popular tourist destinations. Major monuments include Valencia Cathedral, the Torres de Serranos, the Torres de Quart, the Llotja de la Seda (declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1996), and the Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències (City of Arts and Sciences), an entertainment-based cultural and architectural complex designed by Santiago Calatrava and Félix Candela. The Museu de Belles Arts de València houses a large collection of paintings from the 14th to the 18th centuries, including works by Velázquez, El Greco, and Goya, as well as an important series of engravings by Piranesi. The Institut Valencià d'Art Modern (Valencian Institute of Modern Art) houses both permanent collections and temporary exhibitions of contemporary art and photography.

|

History

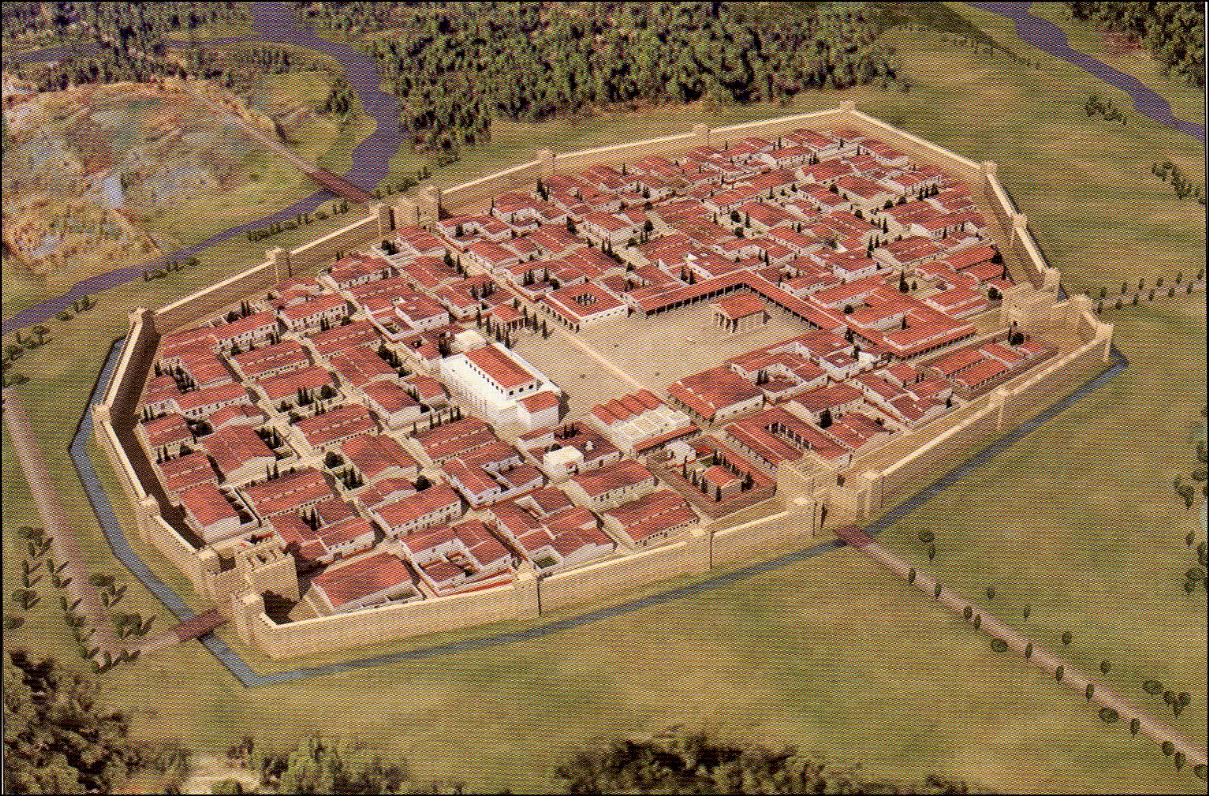

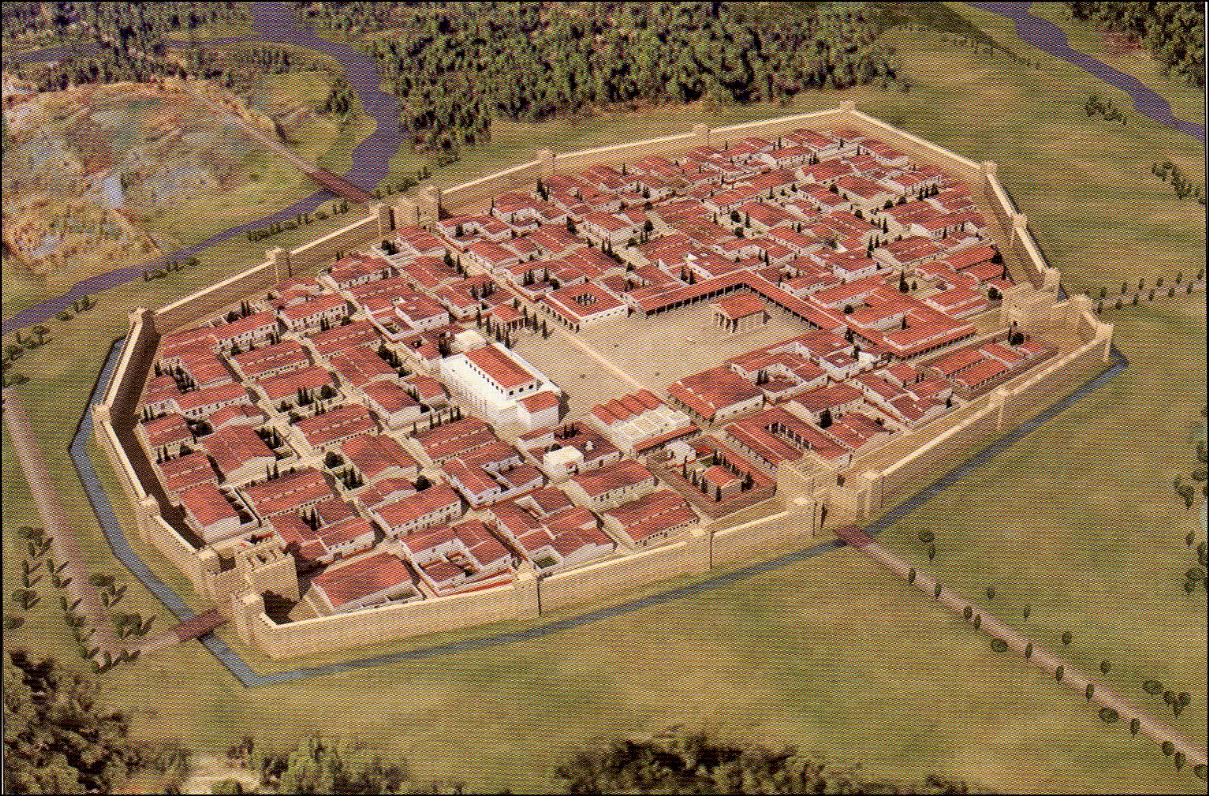

Roman Valentia

Valencia is one of the oldest cities in Spain, founded in the Roman period under the name "Valentia Edetanorum" on the site of a former Iberian town, by the river Turia in the province of Edetania. About two thousand Roman colonists were settled there in 138 BC during the rule of consul Decimus Junius Brutus Galaico. The Roman historian Florus says that Brutus transferred the soldiers who had fought under him to that province. This was a typical Roman city in its conception, as it was located in a strategic location near the sea on a river island crossed by the Via Augusta, the imperial road that connected the province to Rome, the capital of the empire.

Pompey razed Valentia to the ground in 75 BC to punish it for its loyalty to Sertorius. It was rebuilt around fifty years later with large infrastructure projects, and by the mid-first century, experienced rapid urban growth. Pomponius Mela called it one of the principal cities of the Tarraconensis province. Valencia suffered a new period of decline in the third century, but an early Christian community arose there during the latter years of the Roman Empire, in the fourth century

|

|

|

Middle Ages

Visigothic Period

A few centuries later, coinciding with the first waves of the invading Germanic peoples (Suevi, Vandals and Alans, and later the Visigoths) and the power vacuum left by the demise of the Roman imperial administration, the church assumed the reins of power in the city and replaced the old Roman temples with religious buildings. With the Byzantine invasion of the southwestern Iberian peninsula in 554 the city acquired strategic importance. After the expulsion of the Byzantines in 625, Visigothic military contingents were posted there and the ancient Roman amphitheatre was fortified. During Visigothic times Valencia was an episcopal See of the Catholic Church, albeit a suffragan diocese subordinate to the archdiocese of Toledo, comprising the ancient Roman province of Carthaginensis in Hispania.

|

|

Muslim Balansiya

The city surrendered without a fight to the invading Moors (Berbers and Arabs) in 714 AD, and the cathedral of Saint Vincent was turned into a mosque. Abd al-Rahman I, the first emir of Cordoba, ordered the city destroyed, but several years later his son, Abdullah, had a form of autonomous rule over the province of Valencia. When Islamic culture settled in, Valencia, then called Balansiyya, prospered from the 10th century, due to a booming trade in paper, silk, leather, ceramics, glass and silver-work. The architectural legacy of this period is abundant in Valencia and can still be appreciated today in the remnants of the old walls, the Baños del Almirante bath house, Portal de Valldigna street and even the Cathedral and the tower, El Micalet (El Miguelete), which was the minaret of the old mosque.

After the death of Almanzor and the unrest that followed, Muslim Al-Andalus disintegrated into numerous small states known as taifas, one of which was the Taifa of Valencia. Balansiyya had a rebirth of sorts with the beginning of the Taifa of Valencia kingdom in the 11th century. The town grew, and during the reign of Abd al-Aziz a new city wall was built, remains of which are preserved throughout the Old City (Ciutat Vella) today. The Castilian nobleman Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, known as El Cid, who was intent on possessing his own principality on the Mediterranean, entered the province in command of a combined Christian and Moorish army and besieged the city beginning in 1092. By the time the siege ended in May 1094, he had carved out his own fiefdom—which he ruled from 15 June 1094 to July 1099. He was killed in July 1099 while defending the city from an Almoravid siege, whereupon his wife Ximena Díaz ruled in his place for two years.

The city remained in the hands of Christian troops until 1102, when the Almoravids retook the city and restored the Muslim religion. Although the self-styled 'Emperor of All Spain', Alfonso VI of León and Castile, drove them from the city, he was not strong enough to hold it. The Christians set it afire before abandoning it, and the Almoravid Masdali took possession on 5 May 1109. The declining power of the Almoravids coincided with the rise of a new dynasty in North Africa, the Almohads, who seized control of the peninsula from the year 1145, although their entry into Valencia was deterred by Ibn Mardanis, King of Valencia and Murcia until 1171, at which time the city finally fell to the North Africans.

|

|

|

Christian Reconquest

James I the Conqueror, King of Aragon

In 1238, King James I of Aragon, with an army composed of Aragonese, Catalans, Navarrese and crusaders from the Order of Calatrava, laid siege to Valencia and on 28 September obtained a surrender. Fifty thousand Moors were forced to leave. After the Christian victory and the expulsion of the Muslim population the city was divided between those who had participated in the conquest. James I granted the city new charters of law, the Furs of Valencia, which later were extended to the whole kingdom of Valencia. Thenceforth the city entered a new historical stage in which a new society and a new language developed, forming the basis of the character of the Valencian people as they are known today. The city went through serious troubles in the mid-fourteenth century. On the one hand were the decimation of the population by the Black Death of 1348 and subsequent years of epidemics—and on the other, the series of wars and riots that followed.

|

|

Golden Age of Valencia

The 15th century was a time of economic expansion, known as the Valencian Golden Age, in which culture and the arts flourished. Concurrent population growth made Valencia the most populous city in the Crown of Aragon. Local industry, led by textile production, reached a great development, and a financial institution, the Canvi de Taula, was created to support municipal banking operations; Valencian bankers lent funds to Queen Isabella I of Castile for Columbus' voyage in 1492. At the end of the century the Silk Exchange building was erected as the city became a commercial emporium that attracted merchants from all over Europe. Also around this time, between 1499 and 1502, the University of Valencia was founded under the parsimonious name of Estudio General. Valencia was one of the most influential cities on the Mediterranean in the 15th and 16th centuries. The first printing press in the Iberian Peninsula was located in Valencia. The first printed Bible in a Romance language, the Valencian Bible attributed to Bonifaci Ferrer, was printed in Valencia circa 1478.

|

|

|

Early Modern

Spanish Empire

Faced with this loss of business due to the laws governing trade with the colonies which favoured other Spanish provinces, Valencia suffered a severe economic crisis. This manifested itself in several revolts (1519–1523). The crisis deepened during the 17th century with the expulsion in 1609 of the Jews and the Moriscos, descendants of the Muslim population that converted to Christianity under threat of exile from Ferdinand and Isabella in 1502. From 1609 through 1614, the Spanish government systematically forced Moriscos to leave the kingdom for Muslim North Africa. The expulsion caused the financial ruin of some of the nobility and the bankruptcy of the Taula de Canvi in 1613.

|

|

Valencia under the Bourbons

The decline of the city reached its nadir with the War of Spanish Succession (1702–1709) that marked the end of the political and legal independence of the Kingdom of Valencia.

With the abolition of the charters of Valencia and most of its institutions, and the conformation of the kingdom and its capital to the laws and customs of Castile, as a result of the war, top civil officials were no longer elected, but instead were appointed directly from Madrid, the king's court city, the offices often filled by foreign aristocrats. Valencia had to become accustomed to being an occupied city, living with the presence of troops quartered in the Citadel near the convent of Santo Domingo and in other buildings such as the Lonja, which served as a barracks until 1762.

|

|

|

The Valencian economy recovered during the 18th century with the rising manufacture of woven silk and ceramic tiles. The Palau de Justícia is an example of the affluence manifested in the most prosperous times of Bourbon rule (1758–1802) during the rule of Charles III. The 18th century was the age of the Enlightenment in Europe, and its humanistic ideals influenced such men as Gregory Maians and Perez Bayer in Valencia, who maintained correspondence with the leading French and German thinkers of the time. In this atmosphere of the exaltation of ideas the Economic Society of Friends of the Country was founded in 1776; it introduced numerous improvements in agriculture and industry and promoted various cultural, civic, and economic institutions in Valencia.

|

|

Late modern and contemporary

19th century

The 19th century began with Spain embroiled in wars with France, Portugal, and England—but the War of Independence most affected the Valencian territories and the capital city. The repercussions of the French Revolution were still felt when Napoleon's armies invaded the Iberian Peninsula. After the French defeat began six years (1814–1820) of absolutist rule, but the constitution was reinstated during the Trienio Liberal, a period of three years of liberal government in Spain from 1820–1823. Conflict between absolutists and liberals continued, and in the period of conservative rule called the Ominous Decade (1823–1833), which followed the Trienio Liberal, there was ruthless repression by government forces and the Catholic Inquisition.

|

|

|

During the regency of Maria Cristina, Espartero ruled Spain for two years as its 18th Prime Minister from 16 September 1840 to 21 May 1841. Under his progressive government the old regime was tenuously reconciled to his liberal policies. During this period of upheaval in the provinces he declared that all the estates of the Church, its congregations, and its religious orders were national property—though in Valencia, most of this property was subsequently acquired by the local bourgeoisie. City life in Valencia carried on in a revolutionary climate, with frequent clashes between liberals and republicans, and the constant outside threat of reprisals by the troops of General Cabrera. The reign of Isabella II as an adult (1843–1868) was a period of relative stability and growth for Valencia. Services and infrastructure were substantially improved, and a large-scale construction project was initiated at the port.

During the second half of the 19th century the bourgeoisie encouraged the development of the city and its environs; land-owners were enriched by the introduction of the orange crop and the expansion of vineyards and other crops.

|

|

20th century

In the early 20th century Valencia was an industrialized city. The silk industry had disappeared, but there was a large production of hides and skins, wood, metals and foodstuffs, this last with substantial exports, particularly of wine and citrus. Small businesses predominated, but with the rapid mechanization of industry larger companies were being formed. The best expression of this dynamic was in the regional exhibitions, including that of 1909 held next to the pedestrian avenue L'Albereda (Paseo de la Alameda), which depicted the progress of agriculture and industry. Among the most architecturally successful buildings of the era were those designed in the Art Nouveau style, such as the North Station (Gare du Nord) and the Central and Columbus markets.

|

|

|

The inevitable march to civil war and the combat in Madrid resulted in the removal of the capital of the Republic to Valencia. On 6 November 1936 the city became the capital of Republican Spain under the control of the prime minister Manuel Azana; the government moved to the Palau de Benicarló, its ministries occupying various other buildings. The city was heavily bombarded by air and sea, necessitating the construction of over two hundred bomb shelters to protect the population. On 13 January 1937 the city was first shelled by a vessel of the Fascist Italian Navy, which was blockading the port by the order of Benito Mussolini. The bombardment intensified and inflicted massive destruction on several occasions; The Republican government passed to Juan Negrín on 17 May 1937 and on 31 October of that year moved to Barcelona. On 30 March 1939 Valencia surrendered and the Nationalist troops entered the city.

|

|

After the tragic flood of 1957, the city and its economy began to recover in the early 1960s, and the city experienced explosive population growth through immigration spurred by the jobs created with the implementation of major urban projects and infrastructure improvements.

|

|

|

Valencia has experienced a surge in its cultural development during the last thirty years, exemplified by exhibitions and performances at such iconic institutions as the Palau de la Música, the Palacio de Congresos, the Metro, the City of Arts and Sciences (Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències), the Valencian Museum of Enlightenment and Modernity (Museo Valenciano de la Ilustracion y la Modernidad), and the Institute of Modern Art (Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno). The various productions of Santiago Calatrava, a renowned structural engineer, architect, and sculptor and of the architect Félix Candela have contributed to Valencia's international reputation.

|

Tel: +34 963877204

Tel: +34 963877204 Fax: +34 963877205

Fax: +34 963877205 E-mail: int_fi@upvnet.upv.es

E-mail: int_fi@upvnet.upv.es

Valencia, is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third largest city in Spain after Madrid and Barcelona, with around 800,000 inhabitants in the administrative centre. Its urban area extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of around 1.5 million people. Valencia is Spain's third largest metropolitan area, with a population ranging from 1.7 to 2.5 million. The city has global city status. The Port of Valencia is the 5th busiest container port in Europe and busiest container port on the Mediterranean Sea.

Valencia, is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third largest city in Spain after Madrid and Barcelona, with around 800,000 inhabitants in the administrative centre. Its urban area extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of around 1.5 million people. Valencia is Spain's third largest metropolitan area, with a population ranging from 1.7 to 2.5 million. The city has global city status. The Port of Valencia is the 5th busiest container port in Europe and busiest container port on the Mediterranean Sea.